Mishka Henner is an artist based in Manchester, England. He’s been shortlisted for the Prix Pictet and Deutsche Borse Prizes, and was awarded the ICP Infinity Award for Art in 2013. His work is currently being exhibited at the Victoria and Albert Museum, and a solo show recently closed at Carroll/Fletcher in London.

Jonathan Blaustein: You probably don’t know this, but we were both nominated this round of the Prix Pictet prize. For “Consumption.”

Mishka Henner: Okay, right.

JB: I’m going to have a picture in the book. But you were chosen for the short-list. And you will be exhibiting your work at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, yes?

MH: Yes.

JB: I’ve been thinking about it a bit, and since you were short-listed and I wasn’t, I’ve come to believe that it makes you a superior human being to me.

MH: (laughing.) Clearly. Yeah. Although you’ve probably got a better paid job. But go on.

JB: You agree? We can go there?

MH: That I’m superior?

JB: Yeah. To me.

MH: It’s obvious. If I made the short list then you’re a loser. Although come next Wednesday, I may well be the loser. The question is, will I be the bigger loser because it will be on a bigger stage, or a smaller loser?

JB: Nobody even knew that I had been nominated and failed, until now.

MH: (laughing.)

JB: Here’s the way I look at it. I’m prepared to stipulate that you are superior to me, as a human being, and an artist, but your humiliation will likely be larger than mine. Which was heretofore in private. What do you say?

MH: (laughing.) Yeah, I think that’s absolutely right.

JB: Good. I thought we could establish that right away, so that you could realize “Holy Shit. He’s telling the truth. This isn’t a regular interview.”

MH: Yeah, okay. That’s fine.

JB: Good. We’re there now. Well, first of all, good luck. When I saw that Boris Mikhailov and Rineke Dijkstra were on that list, I felt OK about not making it. That’s the big leagues, bro.

MH: I know, I’m well aware of that.

JB: Your ascent seems to have been somewhat rapid, in that you were short listed for the Deutsche Borse prize, and got the ICP Infinity Award. Now the Prix Pictet. How did you get on this many radar screens this quickly?

MH: Fuck, I don’t know. The Internet?

JB: There it is.

MH: I’ve gone viral, I’ve given everyone a virus.

JB: (laughing.) Did you? Go viral?

MH: Well, yeah. I’ve never had a publisher, and I only started working with galleries in the last six months.

JB: Get out. Six months?

MH: Yeah, up to that point, all I’d been doing is print-on-demand books. Books that have maybe sold ten or twenty copies. Those books had a greater life online than as physical books, that’s for sure and a few of them went viral. I did a project called “No Man’s Land,” where I photographed sex workers across Southern Europe using Google Street View.

JB: Right.

MH: That was a print-on-demand book, and I made a just single copy of the book. The pdf was available online and it drew some controversy. A sex worker on the West Coast wrote about it and she was quite positive, but then a load of feminist sex workers on the West Coast basically went ape shit, trying to get the book banned, writing letters to the print-on-demand company.

I had to defend myself to the company’s lawyers and I guess I succeeded because they let me get on with it. After that I sold about 60 books and decided to bring out a second volume.

When the dust had settled I’d sold a few hundred books and “No Man’s Land” was short listed for the Deutsche Borse prize. It’s also the project that was nominated for this Prix Pictet but I didn’t submit it because I was tired of it. I’d been working on the “Beef and Oil” series and thought it would be more interesting to enter that. Nobody had really seen that work properly so I thought it would be interesting to launch it through a prize like that.

JB: You took a risk?

MH: I’d been nominated with “No Man’s Land” for the Prix Pictet for the Power theme two years ago, and didn’t get anywhere with it then. So the risk was that nobody would ever hear about it. Which was fine.

JB: I know how that feels.

MH: (laughing.)

JB: Hey, I made the book. You’ll see it. I’m not a total loser, just mostly a loser.

MH: A mere footnote.

JB: (laughing.) I’ll take that. But just tucking back, when you said the West Coast, you meant the West Coast of the United States?

MH: Yes. But most of the exposure I’ve had has been in the US anyway. In Europe, I’ve had some exposure, and the work has done well, but really, my work’s flying in America. That’s where people are taking notice of the work most and are buying it. The picture editors at the New York Times were my earliest supporters.

I’ve hardly sold any work in Europe.

JB: You guys are bankrupt as a Continent, essentially?

MH: Yeah. But people just don’t buy art here the way they do in the US. Maybe it’s to do with tax breaks, or something else. I don’t know.

There always seems to be something going on in the US about buying art, as opposed to Europe.

JB: You probably could have just stopped that sentence at buying. Right? We’re talking about “Consumption,” and my peeps have sort of perfected the idiosyncrasies of Capitalism. We Americans are proud of it.

MH: Yeah. You’ve done pretty well at it.

JB: And you guys don’t have a lot of disposable income. Even your football clubs are bought by other people. Come on. You’re in fucking Manchester.

Some Americans and some oil sheiks own your shit. You have to know this.

MH: I’m with the oil sheiks.

JB: Of course you are.

MH: That’s right.

JB: Two titles out of three. You’re with the winners. (ed note: Manchester City.)

MH: Look, the biggest photo museum in England has an acquisition budget of £12,000 a year, which is about $20,000. That might just about pay for a cleaner in a US museum. No disrespect to cleaners but that’s doesn’t offer much hope to artists.

JB: It would pay for one square inch of a Gursky.

MH: Exactly. I think that tells you something about the market here.

JB: We went right to the market. But “Consumption,” is the theme for this year’s prize. But we went right to the commodification aspect of Consumption. I’ve spent a bit of time in England in the last couple of years, and went to quite a few museums, which are free. The consumption of art that I saw in London was mind-boggling.

Families and kids and babies and grandmas. Anecdotally, I thought the consumption of art, with your eyes, was much more impressive than I have seen in American major cities.

MH: It’s possible. I think there’s a real hunger for it here, absolutely. And the market for that probably isn’t as developed as it is in the US. I think there are different reasons to do with tax laws, as I said. There are incentives for buying art that probably don’t exist in Britain or Europe.

But listen, I haven’t got a clue. We’re talking about things here that are way out of my league.

JB: I mean viewing. Looking. You must go to London a lot. Do you not notice the hordes that are there to absorb ideas?

MH: Yeah, but maybe we’re talking about different things. It’s true online as well. There’s a voracious appetite for new stuff to look at. It’s a bit like the Tumblr culture, where you’re looking at a waterfall of great stuff. Great imagery, great music. And we absorb it quickly.

We consume it super-fast, and spit it out just as quick. That’s as true in the art galleries as it is online. But as an artist, when it comes to the actual material fact of making a living by selling work, that’s quite different, I think.

Which is more what I was talking about before. We can talk about that other aspect of consuming data, or culture, if you like.

JB: I like to talk about all of it. I was just pointing out the natural way we gravitated. Of course, selling objects is a necessity, if you’re trying to make a living that way.

In America, we have so many more people, and so many more artists, that I think a very, very, very small percentage of contemporary artists even attempt to make their living exclusively through sales.

MH: Sure.

JB: Almost everyone, including the big dogs at Yale, is teaching, or running workshops, or writing. I call it the 21st Century Hustle, because almost everyone has to hustle over here. We don’t have the social service infrastructure that exists in Europe.

I personally live in the Wild West, but I think America is that way. Fend for yourself.

I like to think of the various strands of the process. Why we create? How we create? What we create? And then the market forces are a separate concern. The business and creative concerns rarely come from the same place.

MH: That’s right, and it’s why I’m a bit out of my comfort zone talking about the business side of it. Because I don’t have much experience at that.

In terms of the creation stuff, what was interesting to me about the Oil Fields, especially, is the lineage from John Paul Getty II to Mark Getty. The former was this huge oil baron. He was once asked for the secret to his success and replied, “Rise early. Work hard. Strike oil.”

And Mark Getty, his grandson or great-grandson, is the founder of Getty images. He was once asked why he gravitated towards images as a commodity and said, “Intellectual property will be the oil of the 21st Century.” Or something like that. You should look it up. Anyway, I love that transition from oil to images.

That’s why I became obsessed with oil fields and the idea of even looking for oil fields. In effect, if you think of the world now as a single image that’s been photographed from every angle, from satellites to street view cameras…

JB: Planet Earth is now Picasso’s guitar.

MH: Yeah, it’s an assemblage of images. I like the idea that all this stuff is there, but because there’s so much of it, we can’t see it. Finding the valuable stuff is as difficult as finding oil. When a plane like MH370 goes missing the first place we look is at the satellite imagery because the images of the plane are probably already out there. But just like the ocean is unfathomable, so is the quantity of imagery. We just don’t have the capacity to study it all.

Now, what happened with the feed lots, for me, was fascinating because that’s the work that really went viral in the US. Feed lots are generally remote, in the middle of nowhere and Americans had never really seen them before.

JB: How much time have you spent on the ground in America while you were making this work?

MH: None.

JB: None?

MH: I visited California with friends three months ago for ten days, but that was to see “Spiral Jetty,” Nancy Holt’s “Sun Tunnels”, and Michael Heizer’s “Double Negative.” It was more of a pilgrimage. But apart from that, none.

JB: On I-5, the highway that connects San Francisco and LA, there are strings of these feed lots, right along the highway. You can smell them about ten minutes before you see them, and that stench will carry on for about ten minutes after you’ve left.

So the Californians are familiar with it. It’s not only tucked away in Kansas.

MH: I spent a lot of time looking at California because there are hundreds of feed lots there, but the key ones that struck me were generally in Texas and Kansas because of their size.

Feed lots are pretty much all the same. There are thousands of cattle, you’ve got silos that mix the grain, tracks that allow the trucks to pass up and down dispensing the feed. And then you’ve got these huge lagoons of piss and shit. That’s pretty much a feed lot. I looked at thousands of them. After a while, you start to wonder how big the series should be and I eventually whittled them down to seven key pictures.

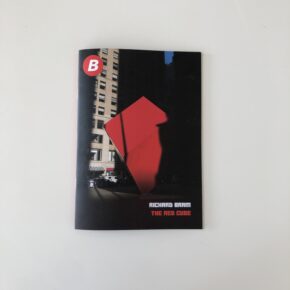

The main one is the one with the huge red pool in the middle of it. The one that looks like a cross-section of a brain.

JB: I just want to say lagoons of piss and shit out loud, because it’s such a great phrase. Now I’ve done it.

MH: (laughing) Well, that’s what they are. People ask, “What’s that?” And I don’t know how to say it really, other than to use those words. Piss and shit is what it is. Hundreds of tonnes of it.

JB: Sure. I’m not mocking you. I’m honest. It’s fun to say stuff like that every now and again.

What do you hope the impact will be on your viewer, when they look at these pictures? What do you want people to think, when they see the picture, read the words, and understand what they’re looking at?

MH: I first came across the feed lots when working on the oil fields. I’d come across the structures and didn’t know what they were. When I started to research them, I was amazed these things existed and would ask myself, “How have we gotten to this point?” The feed lots represent an end point of Capitalism to me. You wonder how much further we can go with it before we destroy ourselves.

But I’ve never seen the feed lots as being just about the cattle in the pens. This is literally a system for living and dying, and I think that system exists beyond the feed lot. It’s a system that our societies, Britain and the US, are aspiring to. The feed lot is almost a dream system. It’s not my dream, it’s my nightmare. But it’s this idea that every sinew of a living animal should be drained dry of productive value. You know what I mean?

JB: I do. They’re concentration camps for cows, really.

MH: With a lot of my projects, the more I spend time working on them, if I think it’s good work, my ideas about it change quite dramatically. From the beginning of the feed lot project, it went from a very practical understanding of what these things were to me thinking that these were systems for living and dying that exist all around us. That we’re actually part of and involved in.

JB: What do you mean by that? That’s an abstract statement.

MH: Well, if you think of yourself as a journalist…are you a freelancer?

JB: I’m a writer, a teacher, and a freelancer writer. I write for this publication, A Photo Editor, every week, so it’s very consistent. And I do a little work for the New York Times.

I’m the person I described before. I’m a little bit of everything, out of necessity.

MH: You might disagree with this but being freelancers we’re trying to make the most of the skills that we’ve got, wherever we can apply them. We’re atomized, in a sense. Our identities are reduced to these productive units.

In England, for example, there’s a lot of discussion about the welfare state. People who work, and people who don’t work. It’s very polarized; ideas of who is worth something in society.

The people who are worth something, generally, are those that are working and productive. The rest are basically draining our resources. They’re a waste of time and space.

It’s an extreme idea for me; an extreme view of life. The idea that every one of us has to be absolutely drained dry. Generally serving someone else’s profit, right?

JB: Yes. Of course.

MH: Taking it back to the feed lot, it’s a perfect demonstration of that. Every single animal in the feed lot, it’s entire life is devoted to serving a single purpose.

Being someone else’s dinner and providing maximal return on someone else’s investment. You can see that way of thinking happening in Britain. It’s less extreme than in the US, but in Britain you can see that thinking applied to the health service. Or to education.

I should probably say I didn’t come from an art background. I never studied art, other than informally. My education was Sociology and Cultural Studies.

In Cultural Studies especially, there’s this idea that you can take a 3 minute Pop song, and in deconstructing and analyzing it, you have the code of the culture. There is a structure, and a code and a language within it that informs how culture works.

I think that’s true of images as well, that maybe there is something locked in the idea of the feed lot, and in these images of feed lots, that stand for something much bigger about the society we’re in.

JB: That’s what we hope to do, when we pick our symbols. Visual Art is about creating symbol sets that speak to larger issues. When you’re good and lucky combined, you might hit on a style of language that makes sense to people.

That was why I was asking what you wanted the viewer to get out if it. It’s clearly very powerful. There’s a lot of solid intellectual underpinning to the interconnection of oil and corn and cows. It’s been sifted through quite a bit, over here in the States.

But your pictures, by combining Internet, Satellite, Surveillance, and then these particular symbols, I think they make it easier for people to comprehend what’s actually going on.

I imagine that’s your goal?

MH: I’m not into artists who lecture, who present their work and accompany it with a lecture about what their intentions and motivations were. Or their research. So I’m reluctant to talk about that and try to keep that out of it.

Obviously I’m talking a lot now and probably saying more than I’d like to, but whenever my work’s presented, I try to say as little about it as I can. There’s the work and then there’s everything else. If I want anything it’s for people who come across the work to really examine it, to figure out for themselves what they’re looking at, and to reach their own conclusions about what’s going on.

I didn’t know, for example, that it was illegal to photograph feed lots, in a lot of US States, because of the Ag Gag laws. So I love the idea that someone who’s confronted with these images is seeing something that has been censored from them. Kept away from them. And all I’m doing is exploiting a loophole, which is that the satellites have already photographed it, and the imagery is out there.

I’m not a vegetarian. So it’s not like I have a very clear goal that I want people to become vegetarian.

JB: Did you decrease your consumption of cows, subsequent to the project?

MH: Yeah. When I was in America, I couldn’t eat beef, because of all the stuff I’d read and seen about it. Most of the beef in the US comes from feed lots so having worked on them and meditated on them for so long, I couldn’t eat it. But I ate chicken. And I imagine the production of chicken’s not much better either. But I didn’t see it, whereas this I could see.

Maybe that’s something: this idea that I’m trying to make something visible that is very difficult to visualize, even if it’s just to help me get to my head around it. But once you do, it can really affect you. That was my idea with the “Oil Fields” as well. On the ground, it’s very difficult to get a sense of the scale of them. But when you go 500 miles up, you can see the scale of them. That was quite shocking to me.

It affected me, and I assumed it would affect others who saw the prints as well. But that’s not something I can really control.

Some journalists have called me an “activist,” but I don’t think of myself as that at all. I think it’s almost disrespectful to activists. I’m an artist and there’s a big difference between the two. I’m not out to persuade anyone or to win an argument.

JB: I can relate to a lot of what you’re discussing. My work went viral when the NYT published it, and it deals with many of these issues. I’ve photographed cows from the pasture to the plate, and then ate them raw.

MH: Really?

JB: Yeah. I photographed a cow being skinned 10 seconds after it was killed from three feet away, with a 50mm lens.

MH: Jesus.

JB: The project that was nominated for the Prix Pictet I did was called “The Value of a Dollar,” and I bought all these food objects, and measured them out, and presented them as is, so it was a reduction of animals as commodity. Comparing the relative value of a handfull of organic blueberries versus a hunk of beef shank that was just a cow leg that someone slapped on a jigsaw and deconstructed.

MH: Yeah, yeah. I’ll look it up.

JB: It just helps give perspective into why I’m so excited about what you did. Your pictures have a palpable ability to impact peoples’ consciousness.

Many artists don’t want to be called “political.” But if your work doesn’t have any sort of political undertone, then you’re not really saying anything.

I’m very interested in how you think of these things.

MH: Well, if you dig really deep down there’s my outrage. I’m pretty outraged about the stuff I see around me. I have strong reactions to it all. And I try to articulate that in such a way that isn’t a rant. If you look at the other work in the Prix Pictet, this is probably the loudest. I think of the image with the red lagoon, and it’s almost like Munch’s scream. Only it’s my scream.

JB: Right.

MH: It’s like a gunshot wound. Or a decapitation. It’s pretty horrific. It’s a pretty strong articulation of my outrage. I really liked what Ed Ruscha said once, that all he wanted to do was photograph the facts. He just wanted to see if it was possible, with his gasoline stations and parking lots and all the rest of it.

JB: Of course.

MH: He wanted to photograph them as facts. I know that’s not fashionable, and there’s been 40 years of photographic critical theory that’s gone against the idea that photographs can in any way be factual, but I like that.

That’s why I love appropriation. It’s using what’s already there. Reframing it changes everything and that can be enough.